Canadian seniors in long-term care were among those most cruelly affected by the pandemic. And for those with dementia, social deprivation proved especially difficult.

Lack of personal contact was also upsetting for the students in Franco Taverna’s human biology class, entitled simply Dementia. This is because students enrolled in the class not only study the brain disorders that lead to cognitive decline; they also visit and develop personal friendships with residents in long-term care facilities, learning first-hand what it’s like to live with conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease or frontotemporal dementia.

With an aging population, dementia is rising rapidly: by 2030, some 1 million Canadians will be affected, with Alzheimer’s disease being responsible for the majority of cases. Since 2008, when Taverna started teaching the course, its social component has grown in importance.

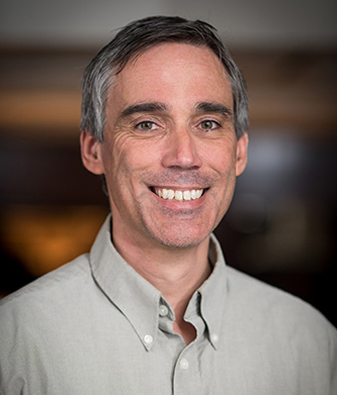

“We study the neurobiology, the pathology, the clinical and behavioral aspects of dementia,” says Taverna, an associate professor, teaching stream, in the Human Biology Program at the Faculty of Arts & Science.

“But dementia’s social and public health aspects, including the study of long-term care models, has become a more important focus in the last few years. We’ve been especially interested in looking at social isolation and loneliness.”

In addition to his background as a neuroscientist, Taverna also acts as special advisor to the dean on experiential learning. He believes strongly that students learn best when they put theory into practice, and this class reflects that.

“In our class, students get to meet people in long-term care, to converse with and become a friend to older adults — some of whom have dementia and are experiencing various challenges,” he says. Over the past 17 years, hundreds of students have become “friendly visitors” at various residences in the Toronto area, such as the Rekai Centres and the O’Neill Centre in Toronto, the Lee Manor in Owen Sound, and several others.

When the pandemic started, however, the visits stopped. That’s when Taverna’s students stepped up on their own.

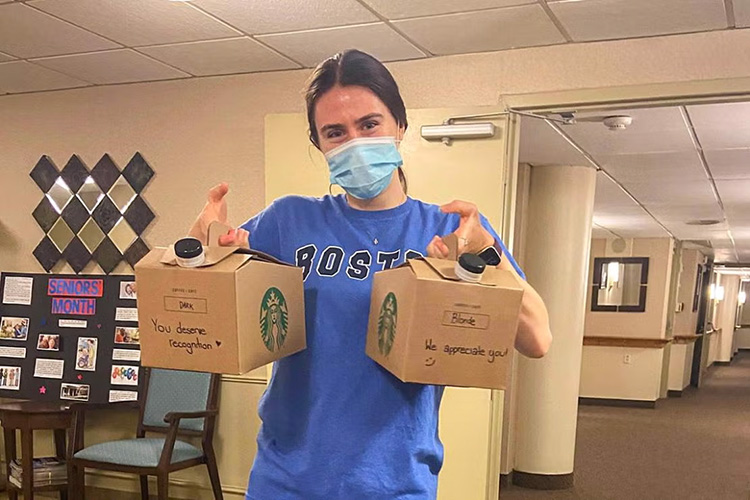

Inspired by the course, which included a memorable class field trip to the Netherlands to learn about an innovative model of patient care, students Rowaida Hussein and Vanessa Rezai-Stevens founded the Student Association for Geriatric Empowerment (SAGE) in 2020 to provide phone calls, snacks and personal notes to patients and front-line workers. Since that time, SAGE chapters have spread across the country, to universities such as Queen’s, Toronto Metropolitan, Western and now Dalhousie.

“This is what happens with experiential learning,” Taverna says. “It can inspire students to do important things in the community. In this case, it’s just phenomenal what they’ve done. Through their inspiration, we’re now up to hundreds of students involved in dozens of events.”

The students’ work inspired Taverna to create CompanionLink, a growing charity that promotes social connections between students and older adults across the country.

Along with commending the efforts of Hussein and Rezai-Stevens, he points out the success that Clémentine Rotsaert has had in taking SAGE into a post-pandemic context.

Rotsaert is a fourth-year member of Innis College, currently completing a double major in physiology and health studies. In the fall, she’ll be entering medical school.

As co-president, she has overseen a wealth of in-person activities with residents in long-term care facilities, such as art workshops, exercise sessions and impromptu spa days. She’s also gotten students from numerous Toronto high school students involved, giving them presentations on dementia followed by visits to long-term care centres. And as a research student with SE Health, a national social enterprise, she’s extended her knowledge of gerontology by using interactive technology to foster connections between patients and care providers.

“An author named Teepa Snow says that people with dementia might not remember their personhood as much as they used to, but emotionally they’re still intact,” Rotsaert says. “So even if you don’t remember your love for a particular activity, you still get pleasure from it. I think it’s really important to remember that people with dementia can still feel happiness and a sense of connection.

“That’s what we try to do with our activities: we bring out those emotions and engage people in the ways they’re capable of, even if it’s limited to who they are in the present.”

Setting up an experiential learning opportunities isn’t always easy, but Taverna says that SAGE’s success proves how worthwhile it is to do so. “There are absolutely challenges and difficulties in doing it, and you have to embrace ambiguity and the unknown,” he says. “But along with the learning you hope to achieve, you also learn to overcome challenges and barriers, to get creative and innovative.”

Rotsaert wholeheartedly agrees.

“I’ve never taken a course with this kind of in-person learning element, and I definitely see how it’s elevated my capacity,” she says. “Most of the time we learn out of context: you learn how something works physiologically, but you don’t see it in practice.

“But it’s extremely valuable to see what dementia looks like — not just to know the neurons and the proteins involved, but to interact with people and see what it looks like in the real world.”